The Final Confessions of the Colonel

A Colonel in American Military Intelligence Discusses Tracking Lee Harvey Oswald Before November 22, 1963, and Other Secrets of the Kennedy Assassination

On a chilly fall day in September 2011, I visited a nursing home just down the road from Bethesda Naval Hospital in Maryland. I was there to conduct one final interview with an old soldier—a man who had led a long and distinguished career in military intelligence. To make matters more challenging, he was also a relative of mine, and my visit would be a final goodbye to a man I greatly admired.

That interview would also change my life and lead me on a long and torturous quest to uncover the true facts surrounding the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, which had occurred sixty-two years earlier.

On the night of November 22, 1963, Kennedy’s body arrived at Bethesda Naval Hospital for an autopsy. He had been assassinated hours earlier while driving through the streets of Dallas, Texas in a motorcade. The government, now headed by Kennedy’s vice president, Lyndon Johnson, deemed it a matter of urgent national security to investigate the forensic, ballistic, and medical evidence related to what had occurred in Dallas’ Dealey Plaza. There were significant concerns that Kennedy had been shot from multiple directions by multiple shooters, which would indicate clear evidence of a conspiracy.

That night weighed heavily on my mind as I sat with my uncle at the nursing home, discussing his life and career in the Army.

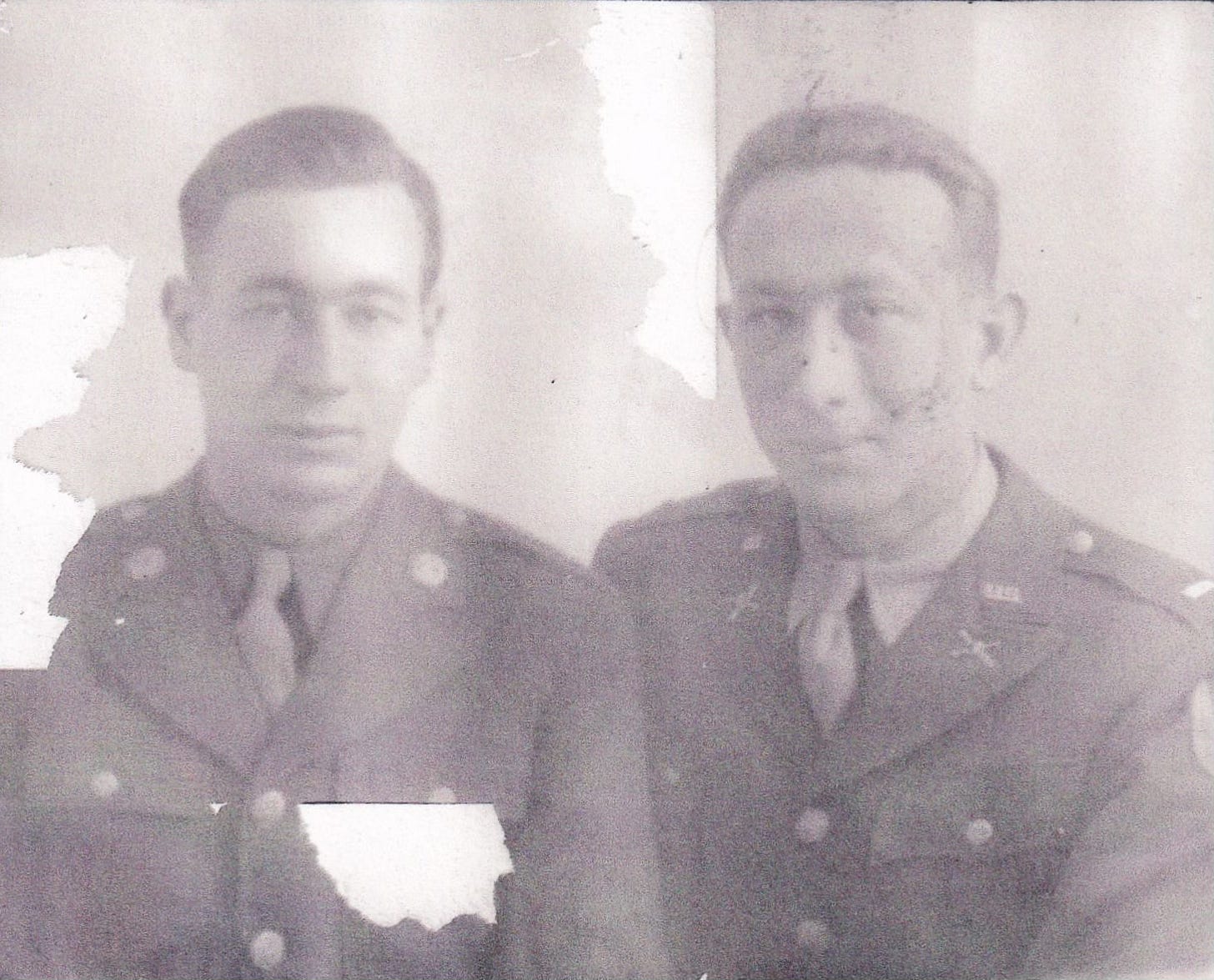

Lieutenant Colonel Gerald Brotman had lived a life reminiscent of an Ian Fleming novel. Growing up in a Jewish household in Germany as Hitler and the Nazis rose to power was, to say the least, a frightening experience. In 1939, the family fled Germany with their lives, eventually making their way to New York City. In 1941, the United States entered World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japan. Gerald and his brother, Walter, were drafted into the US Army and sent back to Europe to fight against their former countrymen.

Colonel Brotman landed at Omaha Beach on D-Day, June 6, 1944, and spent the remainder of the war interrogating captured Nazi officers and generals, including Hermann Göring, the number three leader in the Third Reich’s hierarchy. He smuggled Nazi scientists out of Europe to America as part of Operation Paperclip. He tracked down Nazi war criminals attempting to flee to South America via the clandestine Odessa network. He remained in Berlin as the Cold War—the global power struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union—intensified.

The Colonel then transferred into counterintelligence—spying on spies, as it were—running double agents into Soviet territory and then serving in the Korean War theater. When John F. Kennedy became President in 1960, my uncle was back in Washington, by this time a senior officer. He had a front-row seat to the Cold War entanglements that ensnared the Kennedy administration, such as the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Arms Race with the Soviets, the escalating situation in Vietnam, and other iconic events of that era.

For a book I was working on, I asked my uncle about what he knew concerning the Kennedy assassination. Years earlier, over dinner, when I had broached the subject, he seemed reluctant to discuss it, which only intensified my curiosity. Now, at the end of his life, I hoped my uncle, given his background and experience, would share what he knew about one of the greatest murder mysteries of all time.

He did not disappoint.

In the aftermath of the assassination, the Warren Commission was established to investigate the murder of the President. After ten months of investigation, the Commission released its report stating that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone, without any accomplices, and had an unknown motive for killing Kennedy in Dallas. At the time, the Commission’s report was largely accepted as fact by a compliant press and a traumatized public. However, once scrutinized by independent journalists, researchers, lawyers, and investigators, the Commission’s findings began to unravel like a ball of yarn.

The Garrison Investigation of 1967, depicted in Oliver Stone’s film JFK, uncovered critical leads the Warren Commission missed, revealing a conspiracy involving CIA assets and militant Cuban exiles in New Orleans during the summer of 1963.

By the mid-1970s, the Warren Commission and its report had “collapsed like a house of cards,” in the words of Senator Richard Schweiker.

In 1975, following the Watergate scandal, Congress’s Church Committee investigated major abuses by the FBI and CIA. This inquiry opened a proverbial Pandora’s Box of dark secrets that the intelligence agencies had concealed since the early 1950s. Among the staggering revelations was that the CIA had engaged in numerous illegal operations, both domestically and internationally, including efforts to enlist Mafia bosses in the early 1960s to assassinate Fidel Castro of Cuba. A subcommittee reinvestigated the assassinations of JFK and Martin Luther King and found enough new information to warrant a second official investigation into both murders.

In 1976, the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) was formed to review the findings of the discredited Warren Commission, review old and new evidence, conduct field investigations, subpoena witnesses, and even grant immunity to cooperative suspects.

One of the areas the Committee focused on was Oswald’s relationship with both foreign and domestic intelligence services. The HSCA found that Oswald’s circumstantial connections to agents and assets of the CIA were particularly troubling. Also troubling was the fact that the CIA and FBI knew far more about Oswald before the assassination than they had ever admitted, certainly to the Warren Commission.

Journalist Jefferson Morley recently released a 194-page file on Oswald that the CIA had before the assassination in Dallas. This file revealed that Oswald was under close surveillance by both the CIA and the FBI from the time he defected to the Soviet Union in 1959, through his return to the United States in 1960, and up to the day he shot Kennedy in November 1963.

At the time of the assassination, the CIA’s Deputy Director of Plans, Richard Helms, claimed that the Agency had “minimal information” on Oswald. However, we now know they held a detailed dossier and closely monitored the ex-Marine, particularly during his visits to the Cuban and Russian embassies in Mexico City two months before the assassination.

The HSCA also discovered that American Military Intelligence had its own files on Oswald. When the Committee requested these files from the Department of Defense, it was informed that they had been “accidentally destroyed” during routine archival maintenance.

However, the Pentagon failed to destroy the memory of Colonel Brotman, who not only viewed those files, but had them on his desk months before Oswald shot JFK—demonstrating that, along with the FBI and CIA, even Military Intelligence was tracking Oswald in the lead up to Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas.

The Oswald File

In 1956, a seventeen-year-old Oswald joined the US Marines. He soon found himself stationed in Atsugi, Japan, at a top-secret CIA airbase, where he manned a radar console. Oswald was granted a security clearance at the “Confidential” level; however, as a radar operator at Atsugi, he was able to track the CIA’s new super-secret U-2 spy plane during its flights over Soviet airspace from Japan. Consequently, despite holding a relatively low security clearance, Oswald was exposed to one of the most highly classified intelligence programs of the United States at that time.

Many researchers and investigators, including those involved in the Garrison and HSCA investigations, have long suspected that Oswald, while serving at the CIA’s Atsugi airbase, was recruited by the Agency as an undercover operative. The theory suggests that he was trained in the Russian language and intelligence tradecraft, then urged to resign from the Marines and “defect” to the Soviet Union. He was meant to live in the Soviet Union for a few years and then re-defect to the United States.

As Colonel Brotman acknowledged, there was indeed an active fake-defector program operated jointly by the CIA and the Office of Naval Intelligence at the time of Oswald’s defection. He did not know if Oswald was part of this program. However, it is interesting to note that between 1959 and 1963, no fewer than 60 Americans defected to the Soviet Union and later returned to the United States, often with Russian spouses, as Oswald did.

The CIA has always denied that it debriefed Oswald upon his return to the United States, but Colonel Brotman firmly believed that to be a lie. He said that during the height of the Cold War, it would have been inconceivable for a disgruntled former Marine like Oswald to defect to the Soviet Union, threaten to turn over state secrets to the Soviets, and then return to the United States without being interviewed by the CIA.

Testimony from a CIA case officer seems to corroborate Colonel Brotman’s suspicions.

In 1994, PBS’s award-winning investigative journalism program Frontline interviewed retired CIA officer Donald Deneselya, who recalled reading an agency debriefing transcript of an ex-Marine who defected to the Soviet Union. “I received across my desk a debriefing report,” stated Deneselya. “It was a debriefing of a Marine re-defector. He was returning with his family from the Soviet Union and was back in the United States. The report was approximately four to five pages in length. It gave a lot of details about the organization of the Minsk radio plant. It was signed off by a CIA officer by the name of Anderson.”

The Minsk radio plant is where Oswald worked during his time in Russia.

Frontline corroborated Deneselya’s story using two other sources. The first was a memorandum in Oswald’s declassified CIA file at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Frontline Investigators found that this memorandum contained handwritten notes in the margin that read, “Andy Anderson 00 on Oswald.” The symbol “00” was the CIA’s internal code for their Domestic Contacts Division. Thus, as Deneselya claimed, a CIA officer named Anderson, apparently from the Domestic Contacts Division, had handled Oswald’s files. It is also important to note that the Domestic Contacts Division would have been the appropriate department to debrief someone like Oswald upon his return from the Soviet Union.

Frontline also interviewed the former Deputy Chief of Domestic Contacts for the CIA, who confirmed Deneselya’s story.

Colonel Brotman suspected that the CIA might have maintained some relationship with Oswald following his debriefing. He believed that if Oswald were working with any intelligence service, it would have been the CIA rather than Cuban or Russian intelligence. Although the Colonel described Oswald as a “nut,” an unhinged Marxist-Leninist malcontent, he did not believe Oswald was an agent for either the Cubans or the Soviets.

Lastly, and most importantly, my uncle mentioned that he had seen a military counterintelligence file on Oswald months before Oswald assassinated Kennedy in Dallas. He received the file across his desk. He described it as relatively thin. He skimmed through it without grasping its significance…that is, until after the assassination.

The fact that Oswald’s file reached the desk of a Lieutenant Colonel in Military Counterintelligence, months before Kennedy’s trip to Texas, highlights a significant domestic threat profile that the President’s assassin exhibited. The fact that he was being simultaneously tracked by the FBI, CIA, and Army counterintelligence indicates Oswald was a recognized national security threat.

Despite this clear threat, intelligence about Oswald was not shared with those responsible for President Kennedy’s security, the Secret Service.

On October 9, 1963, FBI agent Marvin Gheesling’s inexplicable decision to remove Oswald from the FBI’s Security Index reduced awareness of his threat level. This action concealed from the Secret Service two key pieces of intelligence: Oswald’s return to Dallas after visiting the Russian and Cuban embassies in Mexico City and his employment at a building along the President’s future motorcade route.

On November 22, 1963, Oswald’s file was still on my uncle’s desk.

A Final Confession

Towards the end of our conversation, Colonel Brotman hesitated, unsure whether he wanted to share something with me. Eventually, he decided to disclose it, but requested that it be off the record, prompting me to stop my tape recorder and put down my notepad.

He recounted a conversation he had with a close friend from a government agency a few years after the assassination. What was said during their conversation shook me to my core. All will be revealed in a book I hope to publish, but suffice it to say that the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, sixty-two years ago yesterday, involved much more than just a murder by a lone, deranged communist named Lee Harvey Oswald.

As I concluded my interview, I realized I was saying goodbye to my uncle for the last time. Months later, he passed away.